Duce Staley's USC career is massively underrated

When we talk about the best Gamecocks of all time, we don’t often mention Duce Staley. But we should.

Once a week, we send out a free edition of To Thee, Forever Ago, and this is it. Put your email address in the box below to have it delivered to your email address every Friday.

In 1988, a middle schooler from the outskirts of Columbia named Lannie Staley received a letter from South Carolina head coach Joe Morrison. Lannie was already a lifelong Gamecock fan. And from that moment on, the USC football program had a hold on the seventh-grader that it would not relinquish, despite fate’s best efforts to pry Lannie loose. The coach who sent him the letter would die of a heart attack shortly thereafter. The coach who subsequently picked up Lannie’s recruitment would get fired. Lannie’s test scores would force him to take a detour to junior college. But seven years, two schools, and one legally changed name later, the young man who had been Lannie couldn’t so much as catch a screen pass at Williams-Brice Stadium without the fans erupting into cheers of DUUUUUUCE!

The exact origins of the nickname Duce aren’t precisely known, even to the Staleys. Their well-informed guess is that it’s either because Duce was the sequel to his father, also named Lannie, or because he was Lannie and Tena’s second child. Either way, as soon as he turned 18, the younger Lannie sought to make it official, legally changing his name to Duce. Why exactly Duce was so keen to make this change is left for us to speculate, but there’s a decent chance it has at least something to do with this: Tena and the elder Lannie divorced during Duce’s adolescence, and Lannie moved 30 minutes away to Pelion. After the move, Duce became estranged from the man with whom he had shared a name. (They reconciled in 2005, in the aftermath of Lannie’s terminal cancer diagnosis.)

Before the divorce, Lannie had been heavily involved in coaching Duce’s youth teams. One thing Lannie told Duce in those happier times stayed with him, even through their 20-year estrangement.

“Son, I want you to win the Super Bowl,” Duce recalled his dad saying. “That's what I want you to do. I want you to make it to the Super Bowl and win it.”

The absence of his father made teenaged Duce “angry” and “rebellious.” But if Duce rebelled against Lannie’s dream that his son become a great football player, the rebellion failed miserably.

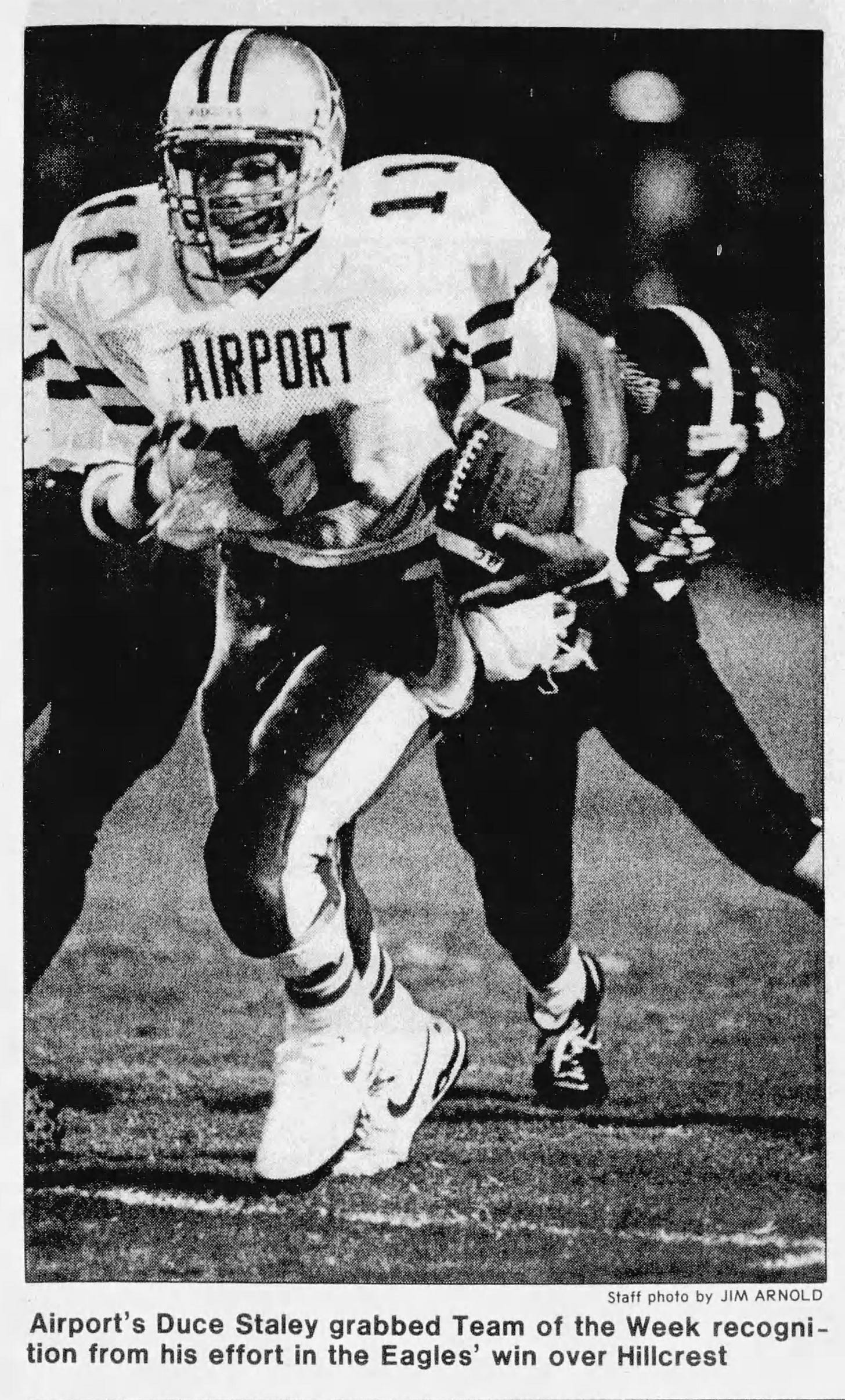

Even as a middle schooler, Duce was getting mail from a college coach in the middle of back-to-back 8-4 seasons. When he moved on to Airport High School, head coach Les Evans observed that the best all-around athlete he saw in 35 years of coaching. During four years at Airport, Duce lined up at quarterback, wide receiver, defensive back, running back, and kick returner. In 1992, Staley was selected at wide receiver as the only unanimous pick for the Associated Press all-state team. That same year, Staley was selected to the Shrine Bowl as a quarterback but spent the game itself lined up at running back, where he ended up leading the victorious Sandlappers in rushing.

When Duce first arrived at Airport, Evans’ original plan was to groom Duce to take over the quarterback position. But Duce was too talented for Evans to keep him off the field until the incumbent starter graduated – and that’s how Duce spent the next five years of his life, including two years at junior college, playing wide receiver.

“By his junior year he was a man among boys as far as his skill and natural moves were concerned,” Evans said in 2001. “That's when we knew we'd see him on Sundays.”

During Duce’s senior year at Airport, it was reported that USC and Clemson were the programs most heavily pursuing him, with Notre Dame, Georgia Tech, Auburn, Pitt, and Tennessee also showing interest. But the major programs, despite their notional interest in a player of Staley’s talent, kept him at arm’s length because of the risk that he wouldn’t qualify.

It was an open secret that Staley’s ACT scores were complicating his college football ambitions. Even after a quasi-commitment to USC in Nov. 1992, Staley said he wouldn’t be fully committed to anyone until he’d been accepted into school. But the qualifying score never came. After signing with Hawai’i in March 1993 – presumably in hopes of ferreting out an easier path to eligibility – Staley made one last try at a qualifying test score for Division I, but once again he came up short.

So Staley packed his bags for Itawamba Community College in Northeast Mississippi, where he first joined forces with a future USC teammate: defensive lineman Patrick Garth. Through Garth, whose last year at Itawamba was Staley’s first, word got back to the Gamecocks’ first-year head coach in Columbia that there was a talented, high-character wide receiver who wanted to come home.

Brad Scott’s time at South Carolina was beset by more bad luck than his harshest detractors ever account for. But one thing that did break his way was Duce Staley. You could not have designed a more perfect running back for Brad Scott’s offense, even if you had done so in a highly effective but ethically suspect genetics laboratory. Scott liked to air it out, and he really liked to throw the ball to his running backs. In Scott’s first three seasons, three different running backs led the pass-happy Gamecocks in receptions. And to look at some of Staley’s more balletic receptions, you might have concluded that he wasn’t a running back who could catch the ball as much as he was a wide receiver who could run between the tackles.

Most of my memories of watching Staley play football were from his days as a pro. So going back and watching him in college to write this article was somewhat jarring. In the NFL, next to other NFLers, Staley looked squat and surprisingly agile for someone as thick as he is. (By the end of his NFL days, Staley was checking in at a robust 5’11, 243.) In college, Staley looks strangely out of place – as if the illustrator drew Staley at his actual size but reproduced everyone else on the field at a miniaturized scale.

Staley himself readily acknowledged that he was never all that fast. What he lacked in straight-line burst, he made up for in an uncanny ability to read opposing linebackers, pick the right holes, and make defenders miss with a well-timed juke or change of direction.

“He's the type of back you want running behind you,'' said Paul Beckwith, the starting center during Staley’s senior season. “Because if you slip up, he will make your man miss, and then he'll make three or four guys on down the line miss … We just give him a little crease, a little seam, and he makes it look like we gave him a big ol' hole.”

But Staley’s talent – though immense – is only part of the equation that explains how he so quickly became a media darling and a crowd favorite. From the moment Staley set foot on campus, he was a go-to quote for every beat reporter – even though he started out the 1995 season as a first-year backup. SEC football teams are often loath to grant media access to newly arrived plyers, so it’s notable that USC made him so readily available in the first place. If you’ve ever listened to Staley talk, it’s not hard to fathom why this would have been the case. Staley is a disarming, expressive communicator and was later able to extend his NFL career at least in part because of how much teammates liked having him in the locker room.

Personality is great, but it only gets you so far unless it’s accompanied by outstanding performances. And the aspect of Staley’s play that won admirers of everyone from the upper deck to the sidelines was his toughness. Not only was it obvious from Staley’s running style that he was giving maximum effort on every down, but it also wasn’t uncommon for Staley to produce his best efforts amid rather hopeless circumstances. One such performance that made a big impression on Brad Scott was the 1995 game against Tennessee. After the 56-21 loss, Staley was described in a way that he often would be described during his USC career: “the lone bright spot.” The junior tailback carried the ball 22 times, gaining a then-career-high 141 yards in a lopsided defeat (it was 35-7 at halftime) that closed the door on any remaining prayer of bowl eligibility.

"That really sticks out for me,'' said Scott entering the next season. "It would have been very easy for a back to say, ‘This one's over. I'm just going to play this out.’ But Duce ran very hard.''

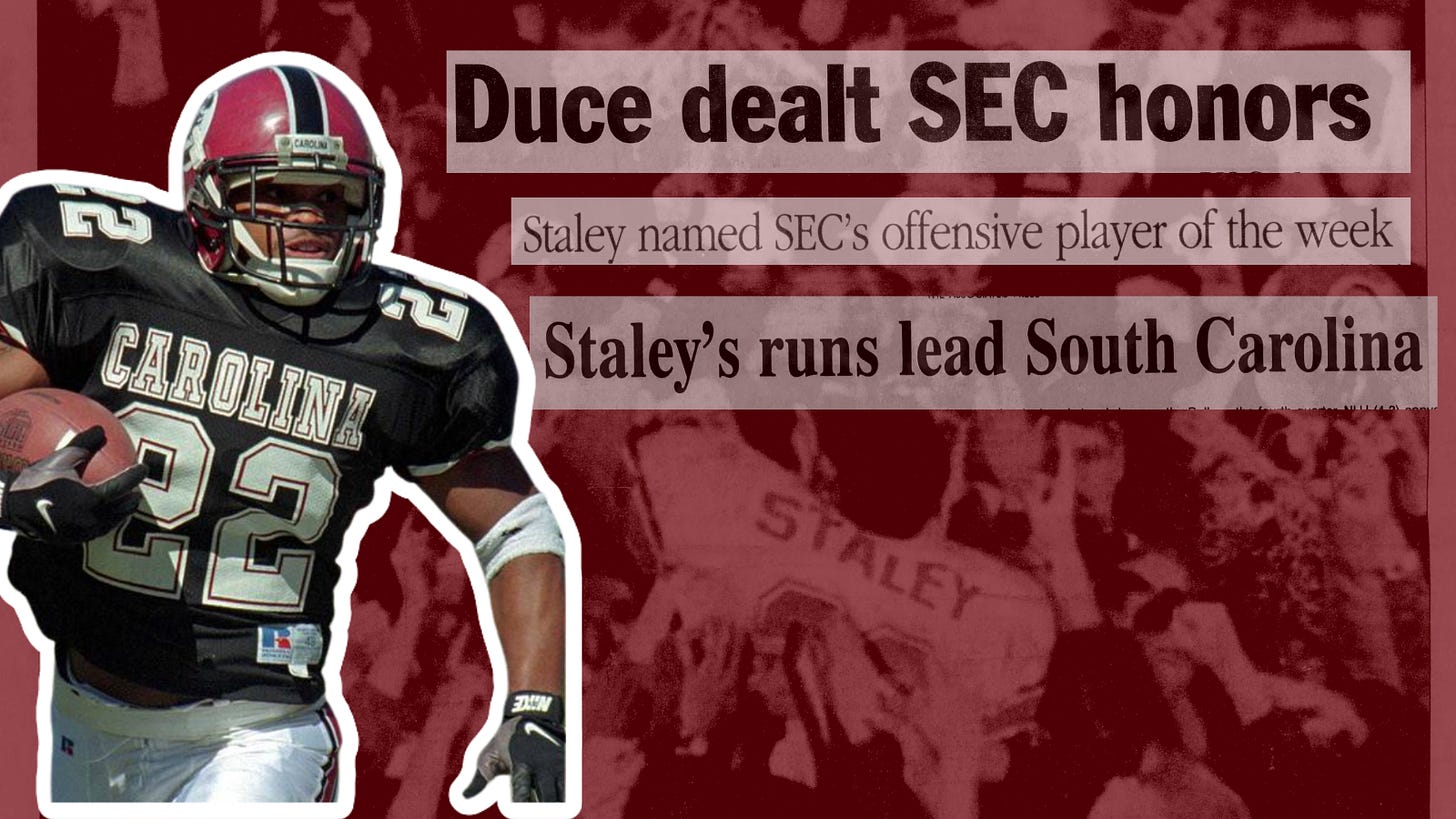

This is the backdrop against which Duce Staley went from being a cult hero in 1995 to something approaching a household name in 1996. Staley’s national hype reached a crescendo after week two of his senior season, when he rattled off 274 all-purpose yards against Georgia, outdueling Robert Edwards, who had terrorized USC with a five-touchdown performance the year prior. With the Georgia performance added on top of a 187-yard, three-touchdown season debut against UCF, Staley came out of the gates on pace to challenge for a 2,000-yard season.

After the Georgia win, South Carolina picked up a handful of Top 25 votes and local columnists were obliquely suggesting – but not quite willing to outright say – that Staley could be a Heisman Trophy contender and South Carolina could be in the mix for a New Year’s Day bowl game. After some growing pains in Brad Scott’s second season, it seemed 1996 might finally be the year that the Gamecocks vaulted into bona fide SEC East contention.

What happened instead was that South Carolina lost the following week … to East Carolina … for the second time in a row. And just like that, the Gamecocks were no longer set up for a season in which they might aspire to greater things than just barely scraping bowl eligibility. They followed up the ECU loss with close-run defeats to Mississippi State and Auburn, and the margin for error on the bowl eligibility scenario collapsed to zero. With mid-November losses to Florida and Tennessee all but certain, USC needed to win each of its four other games, including the finale at Clemson, to have a shot at a bowl.

But even throughout the Gamecocks’ early-autumn swoon, Duce Staley kept on running. Though his per-game average began to taper off, Staley reprised his role as “the lone bright spot.” His streak of 100-yard games (Staley became the first back since George Rogers to string together four in a row) and his quest to become just the fifth-ever 1,000-yard back in Carolina history made for compelling B- and C-plots to an otherwise mediocre season.

The only thing that ever put Staley’s 1,000-yard season in doubt was an ankle injury in the first quarter of an Oct. 26 game against Vanderbilt. Not only was Duce denied the chance to run loose for four quarters against the lowly Commodores, but the ankle injury was so severe that he spent the next two weeks in a cast. Staley missed the entire Tennessee and Florida games, and Brad Scott downplayed the chances that we’d see much of Duce against Clemson. Whether that was gamesmanship from Scott or his genuinely held belief about Staley’s readiness to play, it was indeed big No. 22 taking the handoffs from Anthony Wright on the opening series. And if Staley’s ankle bothered him, there wasn’t much evidence of it in his performance. Along with freshman Troy Hambrick (who’d had a breakout performance in Staley’s absence the week prior), Staley was part of a two-headed rushing attack that took over the game in the second half, with both backs separately scoring two touchdowns and surpassing 130 yards.

“This is what it's all about,” said Staley after the dramatic 34-31 win. “What could be better than this? Except a bowl game."

Despite finishing the regular season 6-5, just as they’d done in Scott’s first season, the bowl invitation never came. The domino effect that shut the Gamecocks out began with No. 9 Tennessee dropping to the Citrus Bowl after the Orange Bowl chose Nebraska over UT. That left the Independence Bowl with a choice between South Carolina and Auburn, and the Tigers had a 7-4 record and a head-to-head win over the Gamecocks. They chose Auburn.

It’s worth wondering how it might have changed the trajectory of Brad Scott’s tenure if he’d made it to two bowl games in his first three seasons. It’s also worth wondering how we’d remember Duce Staley if his Gamecock career had been capped off with the program’s second-ever bowl win — instead of going out, as it did, with a whimper in a bowl committee board room.

In 2015, The State ran a series on the Top 50 Gamecock football players of all time. Not only did Duce Staley not make the cut, but he was also excluded from a sprawling list of honorable mentions that included Rodney Paulk, Stephen Garcia, and Ryan Brewer. My interest is not in relitigating the particulars of The State’s decision to leave Staley off — though that decision was, for the record, clearly incorrect. Rather, I bring this up as a concrete example of a widespread phenomenon in South Carolina fandom: very few people seem to remember that Duce Staley had a truly excellent career at USC.

During his injury-shortened senior season, Staley finished 13th nationally in rushing yardage. He was just the third Gamecock to ever be named first-team All-SEC. He played through an injury to beat a ranked Clemson team on the road. Despite missing two games in 1996, Staley led the team in receptions — ahead of Marcus Robinson and Zola Davis. In two fewer seasons, Staley had 650 more all-purpose yards than Ryan Brewer and nine more touchdowns. Statistically, Duce’s best season has a lot in common with Marcus Lattimore’s best season — in four fewer games.

There’s simply no good reason for underrating Duce Staley as much as we do, apart from the fact that his two seasons came during a stretch of the Brad Scott era that have been lost to the memory hole. 1995 and 1996 neither fit neatly into the story of the surprising success of 1994 nor the calamity of 1998. They were two years when it was still unclear which direction the program was headed. They were filled with equal parts hope and concern. They were two quiet episodes late in the season of a TV show — right before the finale, in which several main characters die, horribly and unexpectedly.

But Duce probably hasn’t even noticed our inability to properly rate his career at USC over the sound of 21 years of NFL paychecks hitting his bank account: 10 as a player, 11 (and counting) as a coach. Though his father didn’t quite hang on long enough to see it, Duce finally did win that Super Bowl — in Feb. 2007, mere months after Duce and Lannie reconciled. He went back and won another in 2018, as assistant head coach of the Eagles.

Staley’s NFL success shouldn’t impact how we evaluate what he did in college. But the more professional accolades he accumulates, the more fresh opportunities we are given to confront a a reality that should have been staring us right in the face all this time: Duce Staley is one of the best players to ever suit up in the garnet and black.

I was teammate of Duce in 93 at Airport. I saw first hand practice and on Friday nights how incredible a player Duce was. My best memory was watching him catch passes at practice. Duce had the best hands catching the football. I remember we would lineup in 2 fullback set on goal line then Duce would run in for TD. Duce had 70 catches for 1000 yards and total 24 touchdowns in his senior year. I hope to see his son Damani Staley playing in Detroit soon and Duce be head coach in the NFL. Gus Monaco Airport Class 1994

I remember the Deuce days very well. 95 was my freshman year. I don't think anyone thought Deuce was gonna be able to play in that Clemson game. I think the ankle injury really overshadowed his final days at USC, and perhaps that's why he's not ranked higher. In my mind he's one of the top backs we ever had.