Dewey Foster and the plane crash that didn't kill Lou Holtz

Twenty-three years ago today, Dewey Foster died in service to his alma mater. When it is remembered at all, the tragedy is too often framed as an example of adversity overcome by Lou Holtz.

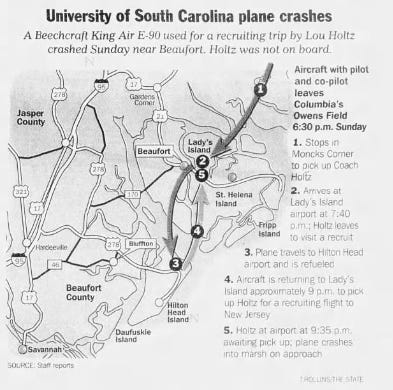

At 8:35 p.m. on Dec. 19, 1999, a small passenger plane on its way to retrieve Lou Holtz for a Beaufort-to-New Jersey recruiting trip disappeared from air traffic control radar. When the National Transportation Safety Bureau filed its final incident report a year later, investigators would note that the plane’s wreckage was discovered just 1.83 nautical miles from the Beaufort airport on Lady’s Island, where it was meant to pick up Holtz. In the coming weeks, news reports would marvel at how narrowly Holtz, dropped off by the same plane 90 minutes earlier, had escaped being aboard its final voyage.

“Why then?” Holtz asked the next day. “Why not when we landed the first time? I don’t know. I really don’t.”

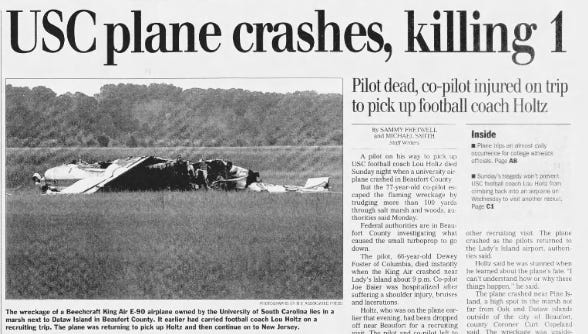

An hour before Holtz and defensive coordinator Charlie Strong showed up to the Beaufort airport, they were on an in-home visit with a Beaufort defensive line prospect. As they sat in the living room of future Clemson star Donnell Washington, the left wing of the King Air collided with the swampy Lowcountry terrain, initiating a violent collision that ripped away the entire landing gear apparatus. The aircraft, now skidding across the ground, crashed into an embankment, which launched the plane into a cartwheel. The somersaults stopped when the plane’s vertical fin caught on the ground, shredding the plane into still more pieces — some of which were found a quarter mile from the initial point of impact. The cockpit and passenger area of the plane finally came to rest in an upside-down position — where it remained until the flames from the ruptured fuel tank devoured the wreckage.

For some, the disaster offered a dizzying glimpse into an alternate timeline. A timeline in which tragedy struck down the would-be savior of USC athletics before his rebuild of the football program was complete — or even begun, really. But for the two men aboard the plane and their families, it was the true version of events — not the imagined one — that proved to be a waking nightmare.

The co-pilot, Joe Baier, unbuckled his seatbelt inside the ruin of the upside-down cockpit, his 77-year-old body falling head-first onto the plane’s crushed-in roof. Miraculously, the only lasting damage dealt to Joe’s body was a broken shoulder. Despite his age, his injury, and the shock of what he’d just experienced, Joe managed to escape the plane and flee to safety before the growing conflagration consumed him.

The pilot, 66-year-old Dewey Foster, never left the plane. The last words anyone heard him say were, “Get me out of here.” But there was no one in a position to grant that last, desperate request. Moments later, the impact of the crash fatally severed Foster’s spine between the C-1 and C-2 vertebrae. For Dewey’s family, the news that he died so quickly was taken as a strange sort of relief, compared to the alternatives: smoke inhalation and burning alive.

The crash made national news, owing mostly to the famous name on the passenger manifest.

“Holtz avoids plane crash,” read the headline in the Miami Herald. “Holtz’s plane crashes,” proclaimed the Cleveland Plain Dealer. In a section for miscellaneous college football news, the Austin American-Statesman — right alongside news of Maryland’s head coach getting a two-year contract extension — noted that the saga capped off a “grief-filled year for Holtz.”

Many papers ran with the angle that Holtz had lost, in Foster, a dear friend. Foster’s family disputes that characterization, describing the relationship as being closer to that of bus driver and passenger. The next week, USC had found a new plane and new pilot, and Holtz was back up in the air.

With one eyewitness deceased and the other convalescing in the ICU, reporters advised the public to expect no further details until the relevant authorities completed their investigations. But by the time the NTSB issued its final report in December 2000, the newspapers had no column inches to spare for Dewey Foster’s final flight. The only outlet that picked up the story of what happened on that overcast evening just outside of Beaufort, was the niche trade publication Professional Pilot.

In the future, the papers would mention the crash only in passing, to demonstrate an example of adversity Lou Holtz had overcome in his fraught 0-11 debut.

“In the fall of 1999, [Holtz] lost his mother, saw his wife and son stricken by illnesses, and providentially missed death himself in a post-season plane crash,” wrote The State in 2002. “In those moments, Holtz might've wondered why he had left a comfortable retirement from coaching, a job with CBS-TV, for this.”

In the moments before impact, Dewey might’ve wondered why he came out of retirement as a brigadier general from the Air National Guard, for this. He might’ve wondered why he kept picking up odd flying jobs — he’d spent several years shuttling around NASCAR’s Cale Yarborough — instead of coasting through his golden years on what remained of his union-negotiated pension from Eastern Airlines. (A pension that Dewey himself joined the picket line to help secure, despite his own personal misgivings about labor unions). Or why he hadn’t contented himself by hanging out at the tennis club — he was a senior circuit champion at the Forest Lake Country Club — and putzing around the house with his wife, Jerry, enjoying life as grandparents and empty-nesters.

On the night of the crash, Dewey and Joe dropped Holtz off in Beaufort and then flew off to Hilton Head to refuel ahead of their three-hour flight to Jersey. (The fueling station at the Beaufort airport was closed for the night.) On the way back to pick up Holtz, Joe radioed in to the Beaufort Marine Corps Air Station to receive headings for their approach into the Beaufort airport.

“How’s the weather?” asked Joe.

“Trace layers at 500 feet, overcast at 1200, visibility five miles with mist,” came the reply. “About the same as your last approach.”

At 8:34 p.m. — one minute before the crash — the Marine Station controller advised Dewey and Joe that they were five miles from the runway. Like many small airports, the Beaufort airport did not have a control tower. It was up to the pilots to activate the runway lights. In these systems, the pilot or co-pilot turns the radio to a pre-set frequency and presses the radio-transmit button on the microphone several times in a row within a five-second span. Upon receiving this message, the runway lights activate and remain lit —usually for around fifteen minutes.

About a minute after last contact with the Marine Air Station, Joe pressed the transmitter seven times.

Click click click click click click.

No runway lights came on.

Twenty-six seconds later, click click click click.

Still no runway lights. The radio, Joe realized, was still set to the Marine Air Station frequency, not the frequency for the Beaufort airport runway light system. Joe turned to tune the radio. In turning, he lost sight of the altimeter and failed to notice the plane falling beneath the minimum descent altitude. Joe felt a violent jolt of impact, the plane’s first contact with the ground.

Baier had been flying USC coaches and administrators dating back to 1979, when Jim Carlen was both head football coach and athletics director. Brad Scott estimated he’d flown with Baier 40 to 50 times. Only recently had Baier moved into the co-pilot chair.

Joe lived three more years after the crash and spent much of that time haunted by survivor’s guilt. Joe wondered if there was more he could have done. How did he, pushing 80 years old, come out relatively unscathed, when his pilot — nearly a full generation younger — had met such a swift and decisive end?

Three days after the crash, Jerry Foster attended her husband’s graveside service at Greenlawn Cemetery. Dewey had specified that he did not want a church service; he was the type of man who didn’t want a big fuss, especially about himself. He was the kind of guy who enjoyed the simple pleasures of a good cheeseburger and a big band record. He would find a shirt he liked and buy fifteen of them.

But the question of whether or not Dewey’s funeral would become a spectacle was taken out of the Foster family’s hands. The attendance of Lou Holtz and Cale Yarborough drew cameras, some of which had camped outside the Foster residence at 8 a.m., the morning after the crash. Once again, Dewey Foster was relegated to a supporting character in the story of his own death.

But the newspapers and the small-time paparazzi moved on from Dewey Foster’s life as soon as he was lowered into the ground. And so did the university he died serving.

There are no statues on the USC campus commemorating Dewey Foster’s sacrifice. There are no multimillion-dollar athletics facilities dedicated to his memory. The university never so much as invited the Foster family to be recognized over the public address system at halftime of a football game. If Dewey’s memory lives on anywhere, it’s in his daughter, Amy, who inherited her dad’s love of tennis and has channeled that passion into coaching high schoolers, building perennial state title contenders at Cardinal Newman and, now, A.C. Flora.

In an age when loyalty is so often measured in message-board upvotes or donations to NIL collectives, the kind of loyalty Dewey Foster displayed — to his alma mater, to his co-workers, to his family, to his country — is a relic of a bygone age. So today, on the 23rd anniversary of Dewey Foster’s death, don’t make a big fuss. That’s not what Dewey would have wanted. But find your own quiet way to serve a cause bigger than yourself, just as Dewey so often did during the 66 years that he lived.

Fantastic work as always, Connor. Great story. I remember the crash well, but knew none of the details. Well done!

Wow., I really don't remember that at all. Great writing, I felt like I was there.