No, Mike McGee didn't turn down the Carolina Panthers

The narrative around how the Panthers ended up playing the 1995 season in Clemson instead of Columbia has been massively oversimplified.

The reason the Carolina Panthers played their inaugural season at Clemson’s Memorial Stadium is because Mike McGee did not want them to play at Williams-Brice Stadium.

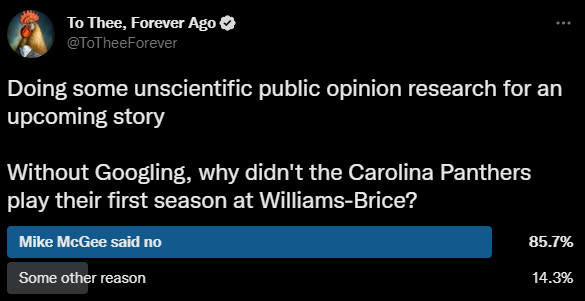

Growing up in the Midlands during the 1990s, this was a piece of information that I absorbed from overhearing adult conversations. Today, if you walk up to any South Carolina fan who remembers the year 1993 and ask them why the Panthers didn’t play their first season at Williams-Brice, they’ll tell you something similar.

There’s a pretty good reason so many people remember this, a thing that absolutely did not happen: trusted local media outlets have repeatedly published an incorrect version of events.

Upon McGee’s retirement from his post as South Carolina’s athletics director in 2005, a web story for local TV station WIS noted that McGee’s “strong opinion against professional sports in Columbia prevented the Carolina Panthers from playing at Williams Brice for a season.” In The State’s memorialization of McGee’s tenure, the paper described McGee as “turning down the Carolina Panthers request to play at Williams-Brice Stadium.”

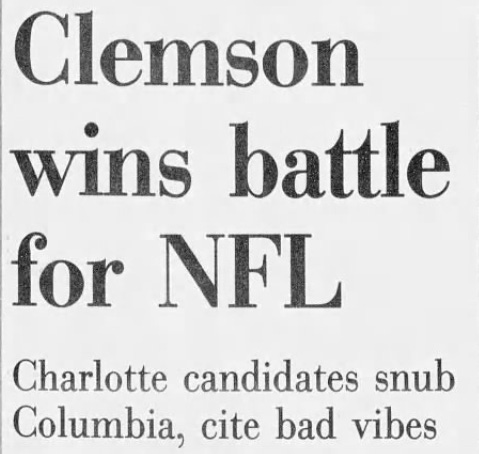

These are demonstrably incorrect characterizations of the 1993 negotiations between McGee and the group bidding for a then-unnamed Charlotte NFL franchise. An easy way to prove this is by showing you The State’s headline from the day Memorial Stadium was announced as the proposed team’s home for the 1995 season.

So what did happen?

Columbia was seen as occupying the pole position from the beginning of negotiations in the spring of 1993 up until the September announcement that Clemson had, in fact, sped right past it on the final lap. The week before the announcement, the Associated Press, backed by on-the-record quotes from Charlotte officials, reported that the expansion bid was close to locking in Columbia as its first-year home. Even after Mike McGee publicly downplayed the profit potential of renting out the Gamecocks’ home stadium to an NFL expansion team, he continued negotiations with Panthers owner Jerry Richardson and his representatives right up until the very end. Two days before Richardson Sports announced its deal with Clemson, McGee and Columbia mayor Bob Coble were confident that they’d put together a package that would work for both sides.

The trouble started in early June after McGee’s first meeting with Charlotte general manager Mike McCormack, wherein McGee voiced his concern that the Panthers might siphon off fans and financial support for the Gamecocks. Not only did McGee raise this issue behind closed doors, he got on the phone with reporters and discussed it with them, too.

“There are only so many discretionary dollars people have,” McGee said in June 1993. “There are some who will elect to support their entertainment through the Charlotte, N.C., franchise. I don’t think there’s any question that will have a negative effect.”

This point of view was publicly endorsed by officials from Georgia Tech, the University of Tennessee, and the University of Miami. It was even endorsed by Clemson athletic director Bobby Robinson in an interview with the Associated Press.

But as negotiations stalled out during the months of July and August, the pressure on McGee began to mount. When The State reported on Sept. 3 that the Richardsons might be turning their focus to Clemson, the Columbia business community exploded with anger. Their frustration escalated further in the aftermath of the Sept. 13 announcement that Columbia had lost out.

“It has nothing to do with money, nothing to do with skyboxes,” said the general manager of the Columbia Marriott. “It is the attitude of the people surrounding the university.”

Long after the particulars of this incident faded from memory, the anger toward McGee and USC remained. And after McGee really did flat-out reject a proposal to move the Aloha Bowl to Columbia in 2001, the two stories eventually got consolidated into one narrative.

Is McGee to blame for missing out on the Panthers?

The assessment of McGee’s conduct best-supported by the facts is that he was negotiating in good faith to strike a deal, but he so badly overplayed his hand that the Richardson oligarchy perceived USC as being unpleasant to work with. (Not to exonerate McGee on this point, but it does bear mentioning that the Richardsons are, shall we say, imperfect evaluators of personal conduct.) McGee probably could have said fewer things — or at least could have said more strategic things — to the media.

And, if possible, he should have put a leash on board of trustees member Michael J. Mungo, who simply could not contain his naked hostility for Charlotte’s NFL bid.

“We’ve got the only game in town, why should we introduce a competitor?” said Mungo, a wealthy real estate developer. “It’s almost like selling a lot to a competitor in the interest of one of my subdivisions. You think I’m that stupid?”

Mungo’s comments made a lasting impression on the Charlotte GM.

“When you see something [like Mungo’s comments] coming from that level,” McCormack said after the decision, “it makes you wonder.”

While McGee himself did turn down individual offers from Richardson Sports, it was always with a view to proceeding toward more favorable terms for USC. McGee never issued a flat-out rejection. But as McGee kept haggling, Clemson was grateful for the honor of being considered. The Tigers’ acquiescent posture was well-received by McCormack.

“When we got [to Clemson], it was almost like they were doing a sales job on us to convince us this was the place that we needed to play and this was the facility we needed to play in,” McCormack said. “They greeted us with open arms.”

So, yes. If McGee had just rolled over and showed his belly to the Richardsons in June, USC would have had a deal. But USC athletics had run at a net loss in 1990 and 1991, the economy as a whole was just coming out of recession, and McGee had just had to hire a new basketball coach — and probably already had an idea that he would soon have to hire a new football coach. So it makes sense that McGee would have fought for a better deal.

Even when Mayor Coble got much more involved late in the process in an effort to salvage a positive outcome for the city, he still endorsed McGee’s haggling.

“If we give them enough latitude so they get a good contract, and don’t force them into prematurely entering a contract,” Coble said, “I think that’s in the university’s best interest and Columbia’s best interest.”

The Richardsons insisted that they didn’t set out to play Clemson and South Carolina off of each other, but that’s exactly what they ended up doing. After spending June, July, and August of 1993 in negotiations with South Carolina, the Richardsons turned their focus to Clemson in early September. Two weeks later, Richardson Sports accepted Clemson’s offer without giving South Carolina a chance to match it. McCormack told The State that it was a financial coin-flip between the schools but that he’d had “disagreeable times” during negotiations with USC, whereas Clemson was rolling out the red carpet.

Was McGee’s skeptical posture justified?

The argument McGee made in public doesn’t make a lot of sense, mainly because it reflected a weird, zero-sum view of sports fandom that doesn’t actually exist. The idea that someone who cared enough about Gamecock football to be a season-ticket holder was going to have their South Carolina fandom displaced by an NFL expansion team seems kind of crazy. And even if some less die-hard fans fell off, it would only be for one season. The new NFL team was going to be located in Charlotte whether they played their first season in Columbia, Clemson, or Cairo; it’s hard to see how eight NFL games would have brought about a lasting diminution in enthusiasm for Gamecock football. You could make — and, in fact, the Richardsons did make — an equally compelling argument that the excitement around the NFL team would have raised overall interest in football and drawn more fans to USC.

Supposedly McGee’s prior experience trying to lure fans from professional sports when he was at Southern California and Cincinnati influenced his point of view on this. McGee had been in Columbia for less than a year at that point, and I think what he failed to realize is that there might be reasons other than the proximity of pro sports franchises to Los Angeles and Cincinnati that accounted for lackluster fan support. And with the benefit of hindsight, we know that Clemson’s average attendance actually went up the year the Tigers and Panthers shared a habitat.

Another thing we know with the benefit of hindsight, however, is that Clemson actually didn’t make much money off their season playing host. An analysis by WYFF found that Clemson netted just $1,971,000, or more than a million less than they expected to. Because South Carolina and Richardson Sports never agreed on a deal, we don’t know what USC might have stood to profit. But we do know that the Charlotte group was demanding an additional $1.2 million in luxury box upgrades beyond what South Carolina was already planning; Clemson already had the requisite luxury boxes in place. If we take Clemson’s profit figure and subtract $1.2 million, we’re getting close enough to this being a break-even proposition that the kind of downside risks McGee was worried about are at least worth considering.

USC should have been more willing to accept a deal, even if the finances were murky

Even if there was no clear profit it in it for USC, hosting eight regular season NFL games and two preseason games would have been great business for the city of Columbia. At the time, low-end estimates had the 1995 NFL season generating an extra $35 million for local businesses. Though the United States as a whole was on the other side of the 1990-91 recession, the national unemployment rate was seven percent, and in South Carolina it was more than half a percentage point higher.

McGee insisted throughout the process that his first priority was to USC, not the city of Columbia. While that’s true, McGee would have done well to remember that USC is rather permanently located in the city of Columbia, so maintaining a good relationship with local officials and business leaders is a worthwhile pursuit.

And then there are the trifling matters of:

Williams-Brice Stadium having been built by a government program

roads to the stadium which are maintained by Columbia and SCDOT

local law enforcement diverting resources to help make home games possible in the first place

But regardless of the finances, it would have just been really cool for people in the Columbia metropolitan area to have a chance to see regular season football right in their backyard. Think of all the people who would now have fond memories of watching the legendary, uh … [checks notes] Vince Workman? … score the decisive touchdown during the Panthers’ first win in franchise history.

TL;DR

Mike McGee could have done a lot better in this situation, but screwing up on accident is a different sort of offense than doing a bad thing on purpose.

Notes

The attentive reader will note that I previously implied that this edition of the newsletter would be the next chapter in the story of how Step to the Rear made it from Broadway to George Rogers Boulevard. As it turns out, there’s a detail in that story that I haven’t been able to confirm quite yet, so I’m holding it in reserve for now.

What I’ve been listening to

The Hard Fork podcast has been doing a good job explaining to me what the hell SBF, FTX, and Binance are.

Michael Hobbes’ new podcast If Books Could Kill, which he co-hosts with Peter from 5-4. The premise of IBCK is: the worst ideas of the last 50 years and the airport books that helped spread them. It’s great!

Michael Hobbes’ slightly older podcast, Maintenance Phase, on how how the agriculture lobby made the Food Pyramid completely deranged.

Michael Hobbes’ former podcast, You’re Wrong About, on the history of the movie ratings system.

My enjoyment of the Extended Michael Hobbes Podcast Universe should not be a surprise to you, since my newsletter could just as easily be titled You’re Wrong About the Gamecocks.

I have also begun tinkering with my world-famous Christmas playlist.