The unfulfilled promise of Ricardo Hurley

Ricardo Hurley was supposed to herald the dawn of a new era in which South Carolina was a national recruiting power. But that's not what happened.

This story was originally published on Aug. 10, 2021. We’re re-running it today, 23 years after Ricardo Hurley signed with the South Carolina. This is your last chance to read it for free. Next week, it goes behind the paywall.

On Jan. 1, 1994, Lou Holtz strode to midfield of the Cotton Bowl and shook the right hand of R.C. Slocum. For the second straight year, Notre Dame had beaten Texas A&M on New Year’s Day. For Holtz, the victory was an exclamation point on his last truly exceptional season in South Bend, and it kept the Irish in the running for a national title.

If nine-year-old Ricardo Hurley watched the NBC broadcast of the Cotton Bowl that day, he would have watched from a town in upstate South Carolina called Greenwood, where he lived with his grandparents. The gathering in the Cotton Bowl was more than three times the size of Greenwood’s entire population, 40 percent of whom lived below the poverty line.

If nine-year-old Ricardo had his grandparents’ TV set turned to NBC that January afternoon, he would have seen a dour, bespectacled man with straw-like hair, impossibly skinny legs carrying a 5’10 frame as it paced up and down the sideline — hands in pockets, shoulders slumped — wearing his signature navy blue pullover and baseball cap emblazoned with an interlocking “ND.” Neither the young boy watching at home in Greenwood nor the millionaire head coach stalking the sidelines in Dallas could have imagined how intimately their paths would soon cross.

Ricardo had a learning disability and had been banned from Pop Warner football for being too heavy. If he was watching the Cotton Bowl that day, he could not have dreamed that he would soon welcome the man on TV into his living room. That the college football legend would sit across from him, now in a black pullover and a garnet cap, and make one last desperate pitch the week before National Signing Day. Nor could he have imagined that his decision to sign with Holtz and South Carolina would herald the Gamecocks’ arrival as a national recruiting power, with Hurley as its crown jewel. Or that, just as quickly as Hurley’s and USC’s fortunes had each turned for the better, so too would they take a turn for the worse.

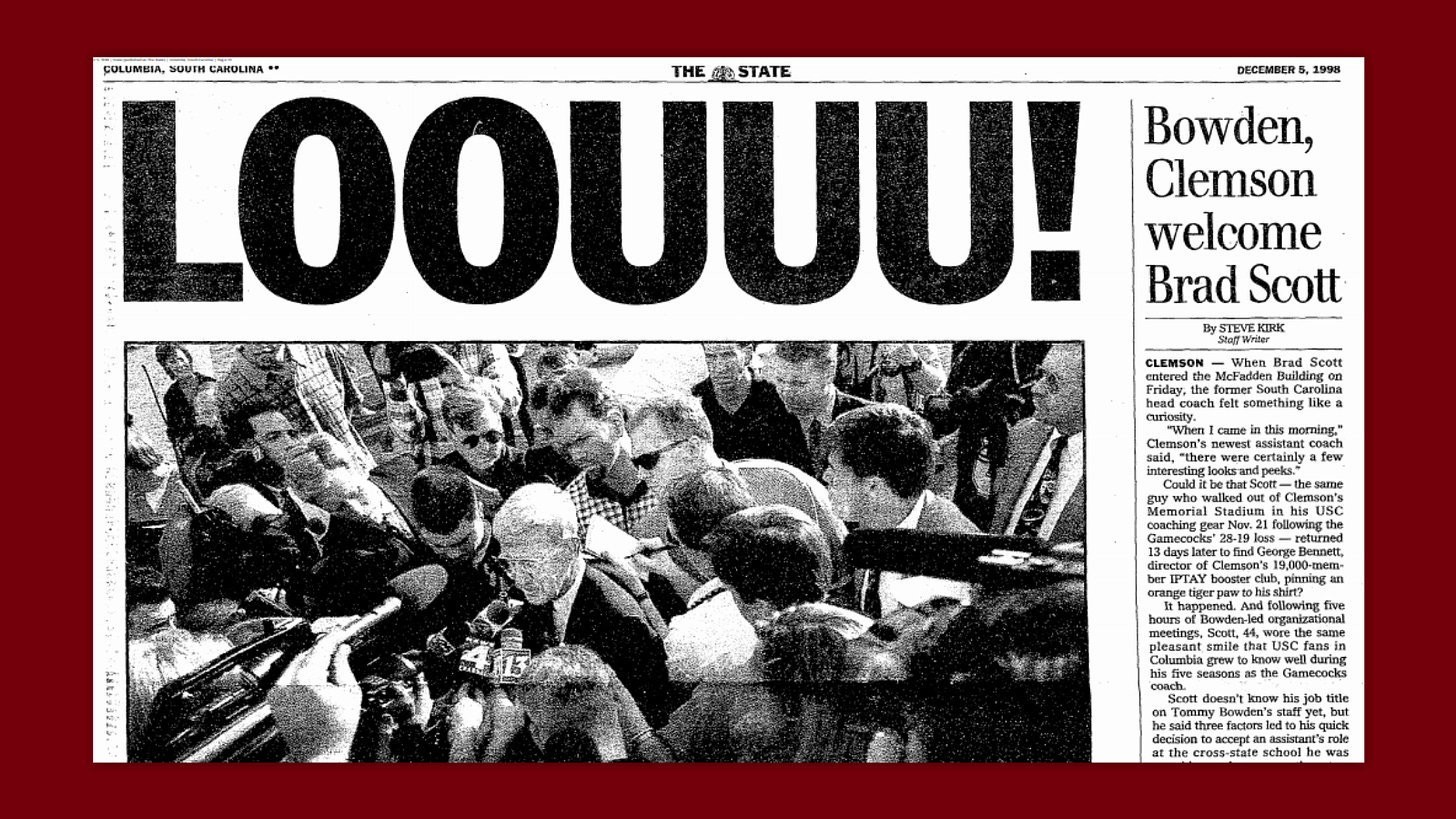

Lou Holtz revives South Carolina

During his introductory press conference in Dec. 1998, Lou Holtz admitted, “A lot of people said, ‘You can't win at South Carolina and you're making a big mistake if you go there.’” At the end of his first full season, it looked like those people were onto something. The Gamecocks showed some pluck on their way to an 0-11 record, but they were 0-11 all the same. Now, their 21-game losing streak was the longest in the country.

A more sensible brand of non-conference scheduling in 2000 made it all but certain the streak would end in the first three weeks of Holtz’s second season, and it did. But it wasn’t until a five-interception performance from Charlie Strong’s defense against No. 10 Georgia that it first seemed Holtz’s USC project might amount to something more than a fun little hobby to keep him busy during his golden years. The Gamecocks raced out to a 7-1 start and climbed as high as No. 17 in the AP Top 25. But it all came crashing down, as it often did, during what fans had taken to calling The Orange Crush. That is, the three-game stretch of schedule featuring consecutive matchups against Tennessee, Florida, and Clemson, which had closed out the season every year since joining the SEC in 1992.

By the turn of the century, there was an understanding among the USC fan base that the team had better get bowl-eligible in October, because leaving win No. 6 until November was a fool’s errand. Only once had South Carolina emerged from The Orange Crush with more than a single win, and USC lost all three in five out of eight attempts; the 2000 season made it six out of nine. But a comprehensive 24-7 win over No. 18 Ohio State in the Outback Bowl halted the skid and revived the positive momentum from the 7-1 start. With the program’s first ranked finish since 1987, there was no painting the season as anything other than a massive success.

The 2001 season saw the program take another step forward. This wasn’t just a winning team; it was, occasionally, a dominant one. This time, USC started the season in the Top 25 and never left. And for the first time since 1996, they beat Clemson. But on the way to a 9-3 record, the team got a taste of something it did not expect: the possibility of winning the SEC East.

South Carolina entered the second week of November with a chance to beat Florida and claim its spot in a three-way tiebreaker between UF and Tennessee. But after a week of hype leading up to College GameDay’s first trip to Columbia, Steve Spurrier’s Gators thoroughly outclassed USC in a 54-17 beatdown that laid bare just how far the Gamecocks still had to go if they ever hoped to truly contend for SEC hardware.

Holtz had done a commendable job building a reliable winner out of spare parts and duct tape. But if this project was ever going to make it to the next level, there was no getting around one central fact: Carolina needed better players.

There were a handful of players in Holtz’s first two classes who went on to form the spine of his best teams: Dererk Watson, Travelle Wharton, Ryan Brewer, and Dunta Robinson, to name a few. But top-to-bottom, South Carolina’s classes were filled with players nowhere near the caliber signed by Florida and Tennessee. And it was well-understood that the Palmetto State’s very best players would almost always flee to out-of-state superpowers. In 2000, for instance, FSU imported three of its top signees from South Carolina. In the event that blue-chippers did elect to stay close to home, they were much more likely to choose Clemson, as five-star wideouts Roscoe Crosby and Airese Curry did in 2001.

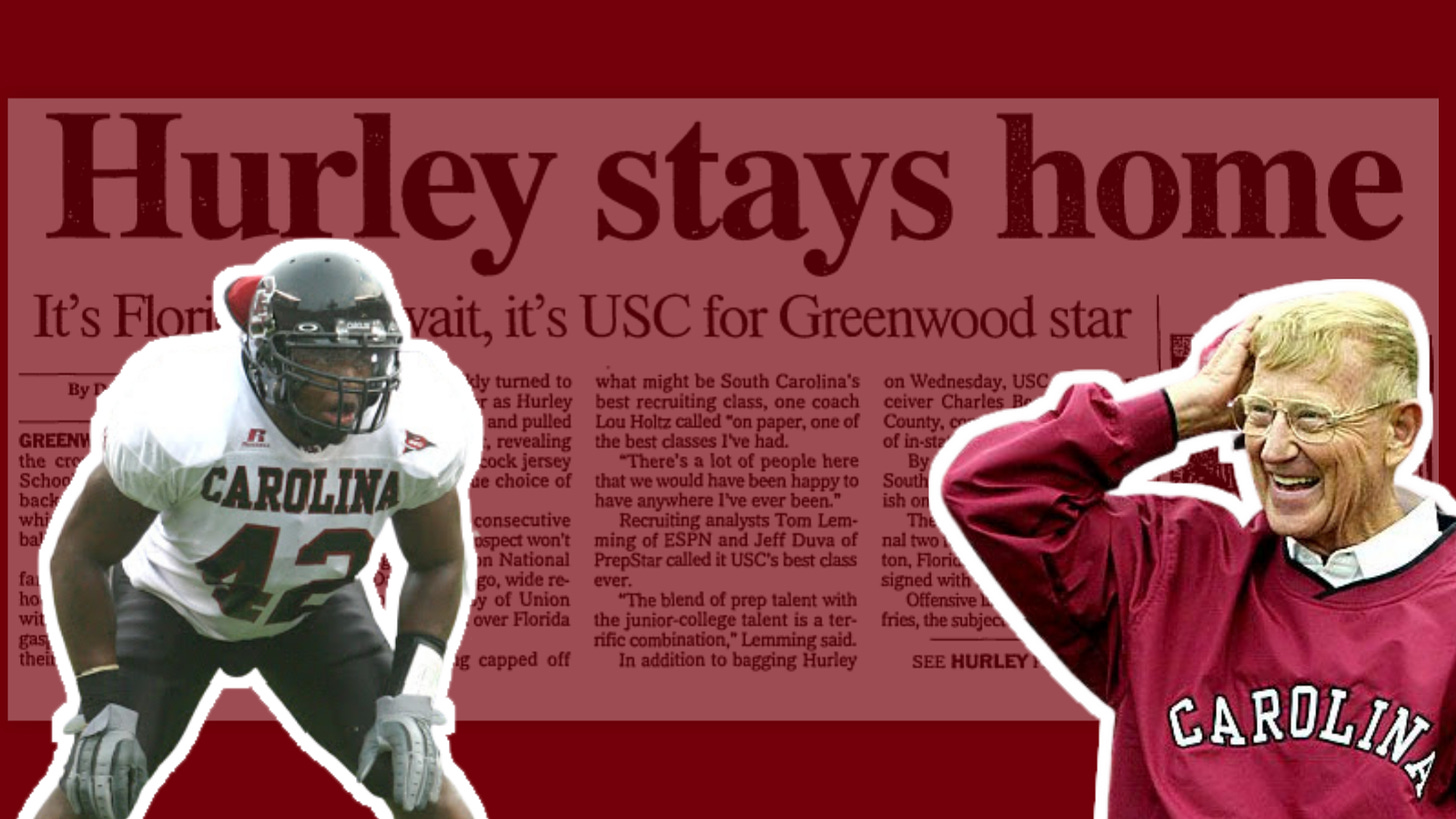

On National Signing Day 2002, that seemed poised to change. The Gamecocks had signed the No. 7 class in the country, according to ESPN. The group featured a mix of readymade JUCO transfers and a strong crop of in-state players, including future top-10 NFL Draft pick Troy Williamson, 2001 Mr. Football Moe Thompson, and future two-time All-American defensive back Fred Bennett.

But all analysts agreed that the pièce de résistance was a five-star linebacker from Greenwood named Ricardo Hurley.

The Rise of Ricardo Hurley

Because he exceeded the maximum weight to play Pop Warner football, Ricardo Hurley didn’t play football until seventh grade.

“I got teased a lot,” Hurley reflected in 2001. “People were calling me fat boy, stuff like that ... It was pretty painful.”

But in high school, Hurley’s doughy body transformed into a 6’3, 235-pound ball of sinew. When he was finally united on the football field with his older (but physically smaller) brother Ricky Grant, Ricardo relished the opportunity.

“I waited a long time to play with him,” Hurley said. “All while I was coming up.”

Before an important game against Spartanburg in 1999, Grant and Hurley slept the night before in their jerseys and helmets.

“It wasn't comfortable, but we were ready,” Grant recalled. “We were trying to get our minds right. That's just how we were.”

During Hurley’s 98-tackle, 17-sack junior season, Hurley and Grant formed one of the best linebacker tandems in the state. Ahead of Greenwood’s second consecutive state championship in 2000, head coach Shell Dula said his entire defensive strategy was oriented around freeing up “the Bash Brothers” to make big plays. And it was often the case that Greenwood’s opponents oriented their entire offensive strategy around avoiding Hurley.

“The game plan was to stay away from No. 42,” said T.L. Hanna head coach Scott Parker after a 56-22 loss to Greenwood in 2001. “We didn't want him hitting any of our people.”

Grant was a Shrine Bowl selection in 2000 and signed with USC the next February. But he didn’t have the grades for Division I, so Lou Holtz’s staff placed him at Georgia Military Academy. The implicit understanding in such arrangements is that the placed player will, at a minimum, be given premium consideration to return to the school that placed him once he meets the academic requirements. So as Hurley’s profile rose going into his senior season, this gave South Carolina an in-road that FSU, Georgia, and Florida could never hope to have. Hurley didn’t know then that Grant would never end up qualifying to enroll at South Carolina.

Hurley first appeared in Phil Kornblut’s recruiting column on March 12, 2001. (Waiting until the spring before a prospect’s senior season to write about him through the lens of his potential value to a college program — how quaint!) Over the summer, a favorites list emerged that included USC, Georgia, Georgia Tech, Tennessee, Florida State, and Florida.

That fall, Hurley followed up his eye-popping junior season with a solid but less-spectacular senior campaign. He was the must-see attraction of the 2001 Shrine Bowl, where he dominated in the week of practice leading up to the game.

“We ran a little trap and there he is,” said Lancaster High coach Johnny Roscoe, the head coach of the South Carolina Shrine Bowl squad. “I was, ‘Where'd he come from?’ I went over to one of the coaches and said, ‘Man, did you see that?’”

The praise wasn’t just coming from within the Palmetto State. Rivals.com ranked him the top linebacker in the class of 2002 and the No. 17 player overall.

“It’s a great year for big linebackers,” wrote Bobby Burton of Rivals. “Hurley, the top prospect in the state of South Carolina, is considered the best of the bunch. His combination of size, speed, athleticism and playmaking is unmatched.”

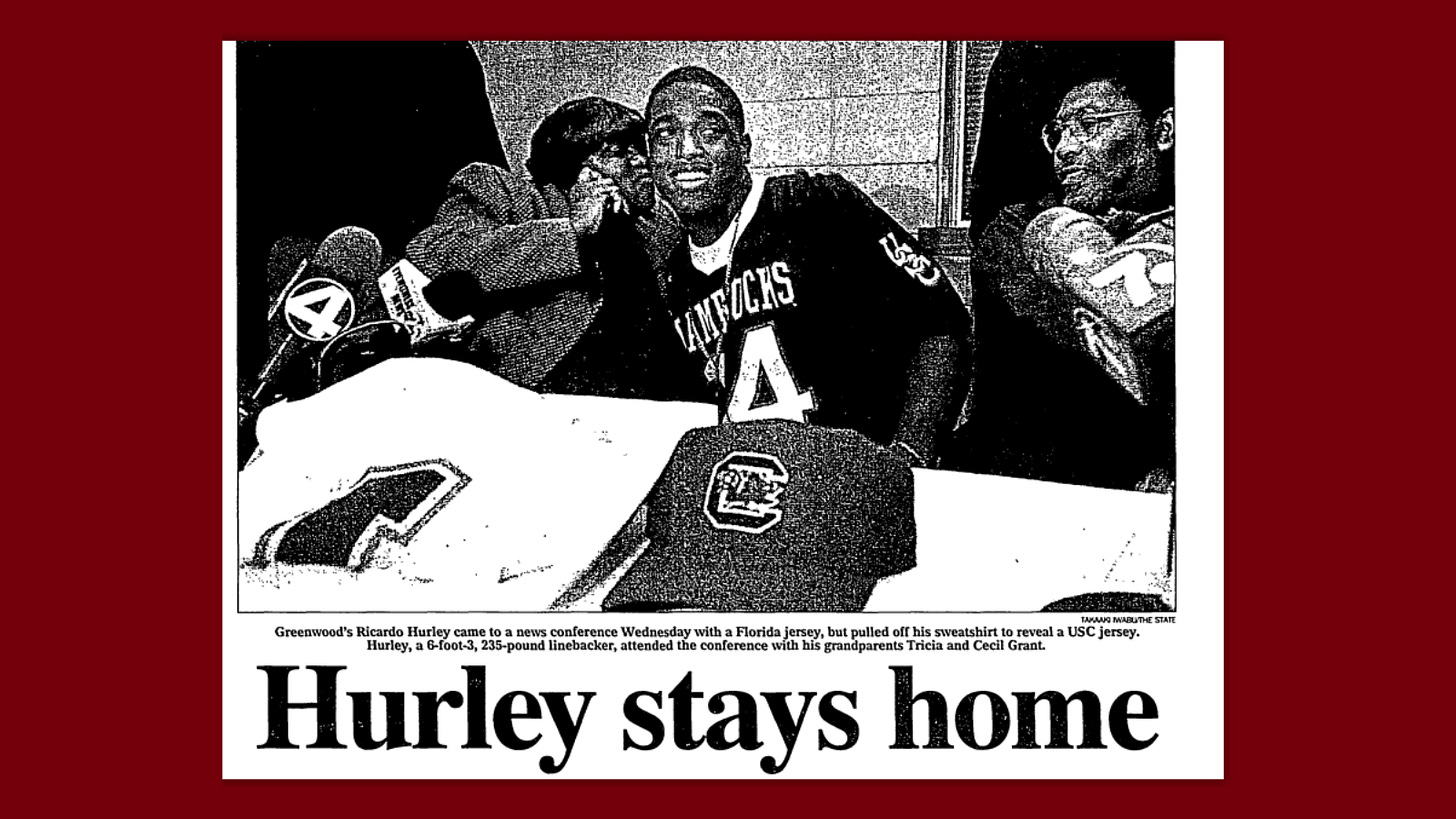

In the end, Hurley visited USC, Georgia, and the Florida schools, with the Gators getting the last word on a Feb. 1 trip to Gainesville. Heading into Signing Day, Hurley winnowed his list down to USC and Florida. At the announcement ceremony, he sat behind a table, flanked by his grandparents, his head coach, and his defensive coordinator. Hurley pulled a Florida jersey out of his bag, and the assembled crowd drew in gasps of astonishment. They let out sighs of relief and laughter when Hurley discarded it and removed his grey sweatshirt, revealing a black South Carolina jersey underneath.

“Hurley said he chose USC because he liked the idea of playing close to home where his grandparents, who raised him most of his life, and friends could watch him play,” wrote David Newton in The State. “He said the atmosphere at Williams-Brice Stadium and a promise by Holtz that he wasn't leaving any time soon also played a factor.”

Hurley said he felt “at home” and looked forward to being joined by his brother in 2003.

“Coming into Greenwood High School [Ricardo] had a dream of things he wanted to do,” said his high school defensive coordinator. “He had come from a situation that was not real easy, but he had somewhere he wanted to go and he worked for it.”

Later that night, Hurley, as he did most days after football practice, punched in for his four-hour shift as a cook at Captain D’s.

The wheels come off

There’s a case to be made that Ricardo Hurley’s Signing Day announcement was the precise moment that the Lou Holtz Era peaked. Following up the best two-season stretch in program history, South Carolina was, so it seemed, setting itself up for sustained success by leveraging its on-field results into bringing higher-quality players.

“Having recruits watch you win a bowl game is a plus, but in my opinion having Lou Holtz walk into your living room is a hell of a lot more impressive than seeing a bowl game,” said Tom Perrone of Prep Atlantic. “He's done an excellent job recruiting kids and if he stays three, four or five more years, South Carolina is going to have a solid foundation because of the way Lou recruits.”

But the remainder of USC’s offseason was a disaster. First, star running back Derek Watson was dismissed from the team. It even looked for a while that Hurley wouldn’t qualify academically — but in the end he was granted a hardship waiver by the NCAA, owing to a medically diagnosed learning disability.

In what some imagined would be a step forward for the USC offense under dual-threat quarterback Corey Jenkins, the Gamecocks instead were an uninspired, interception-prone mess. Despite not remotely passing the eye test, Carolina nevertheless managed a 5-2 start through mid-October. But then The Orange Crush hit, and the Gamecocks lost five straight games to close out the season. At the end of the year, star defensive coordinator Charlie Strong left for the University of Florida.

It was a similar story in 2003. The Gamecocks had five wins at the end of October but once again went 0-for-November. In 2004, USC finally got back to six wins by defeating Arkansas in a 35-32 thriller, the team’s first November win since 2001. But both Clemson and Carolina withdrew themselves from bowl consideration following the brawl in Death Valley on the last week of the season.

The Clemson debacle was the last time that Lou Holtz’s impossibly skinny legs would carry his 5’10 frame as it paced up and down a sideline — hands in pockets, shoulders slumped — wearing his signature black pullover and garnet baseball cap emblazoned with “Carolina Football.” As Holtz weighed his decision to retire, if the promise he’d made to Ricardo Hurley in 2002 factored into his thinking, it did not change the outcome.

As USC’s fortunes declined, so did Hurley’s. After a strong true freshman season, a severe ankle sprain shortened his 2003 campaign and slowed him down thereafter. For a big linebacker in a league at the dawn of a spread offense revolution, this diminished mobility would cost him dearly. Hurley’s progress was also slowed by a move to outside linebacker, where he felt less comfortable. Nevertheless, Hurley started all 11 games in 2004 and had a chance to revive his status as an NFL Draft prospect during his senior season under a new head coach. At first, Hurley welcomed the change.

“We didn't have the right coaches,” Hurley said in 2005 of the staff at the end of the Holtz era. “We had some good coaches, but they made things a lot more complicated back then, a lot more complicated for the players. I don't feel like I was coached like I was supposed to be.”

Steve Spurrier’s defensive staff decided to move Hurley back to middle linebacker, which Hurley was excited about. But seven games into his senior season, Hurley was benched for a sophomore. Benched for a sophomore by a coach hadn’t recruited him and with, as Hurley saw it, no explanation.

“I was the second-leading tackler on the team,” Hurley said, when asked why he’d been benched. “I thought I was doing something right. All that just hit me at once. I didn't know what was going on really.

“So I really can't say nothing about it, but … I was asking that same question myself.”

Co-defensive coordinator John Thompson, who coaches the Gamecocks' inside linebackers, would not discuss the specifics of Hurley's demotion.

“You do that at every position. You just get people out there that you think are doing the job,” Thompson said. “And Ricardo's still doing it.”

As for Hurley's contention that he was not told why the move was made, Thompson said: “There are some things that people understand and some people don't understand.”

Among armchair and barstool coordinators, the feeling is that Hurley was over-running and missing too many tackles while struggling to pick up the new scheme.

Hurley did not dispute the former theory, but he shot down the latter.

”That's football. Everybody misses tackles. You see a lot missed tackles in the game last week,” he said. “When you're playing fast you're going to miss tackles.”

Hurley said that he knew the scheme and was comfortable in it.“He still plays a lot. He's hustling. He's trying,” said USC coach Steve Spurrier, noting that Hurley was in for 25 snaps at Arkansas. “(The demoted players) have all had pretty good attitudes about it. Hopefully, they realize that they weren't playing all that well to stay in there.”

Hurley, who along with former tailback Demetris Summers were the only Parade All-Americans signed by USC coach Lou Holtz, has not abandoned his NFL dreams.“He is very talented,” said Thompson, who called Hurley a workhorse. “All of that will come down the line, and we'll do everything we can to help him.”

Hurley technically did have an NFL career. Cleveland signed him as an undrafted free agent in 2006. Seven weeks later, the Browns released him.

And so it was that Ricardo Hurley came to be remembered not for what he was but what he could have been. When South Carolina fans think of Ricardo Hurley — if they think of him — they mourn the promise that he never lived up to. Little mind is given to the promises made to Ricardo that others did not live up to. In hindsight, the one aspect of South Carolina’s recruiting pitch that it hadn’t reneged on was that Columbia was still just 90 minutes from Greenwood.

But even after it had become clear that Ricardo would never be the transformational player South Carolina fans once dreamed he could be, he still had one final contribution to make. In 2005, USC entered November with only five wins. With Clemson and 12th-ranked Florida looming, the Gamecocks were holding on to a 14-10 lead against Arkansas in the last five minutes of the fourth quarter. The Razorbacks had the ball on the Carolina 17-yard-line for 2nd-and-1 with Darren McFadden in the backfield. Against all odds, the Gamecocks produced three consecutive short-yardage stops, including two from Hurley, to force a turnover on downs and lock up their sixth win.

Meanwhile, in a town called Greenwood — with a population one-third the size of the crowd gathered in Razorback Stadium, 40 percent of whom lived below the poverty line — there lived a 14-year-old boy who considered Ricardo Hurley and Ricky Grant his role models. He’d just begun his freshman year at Greenwood High School that fall, and the next year he became a two-way starter for the football team on the way to a state title — Greenwood’s first since the days of the Bash Brothers. In 2008, he’d follow in his role model’s footsteps and commit to the University of South Carolina, helping to start a trend of the Palmetto State’s best players going to USC. And when he faxed in his National Letter of Intent in Feb. 2009, the signature line read, “Dayario Jamal Swearinger.”