On loving and mourning a difficult dog

Last week we said goodbye to Rilo, a real piece of work who lived to the unbelievably old age of 16.

Adopting Rilo was, by any objective measure, a grievous error. First, there was the dubious wisdom of getting a dog at all. Then, there was the question of getting one together: at the time, Annie and I had only been dating for eight months. There was also the small matter of our leases expressly forbidding dogs.

In the end, adopting Rilo threw our housing status into chaos just a month before the start of our senior years at USC. Eventually, it led to Annie and I cohabitating far earlier than we otherwise might have.

In addition to those burdens, there was of course the hard work of training, providing for, and loving an underweight, worm-infested puppy. (Rilo and her littermates had been separated from their mother and discovered in a trash can by a soldier who’d just returned from a tour in Iraq.) But that litany of good reasons not to get a dog never stood a chance against the four-pound pup climbing on top of its eight brothers and sisters, as if to say, pick me pick me.

But like some unknowably small percentage of terrible mistakes, this one turned into one of the best decisions we ever made.

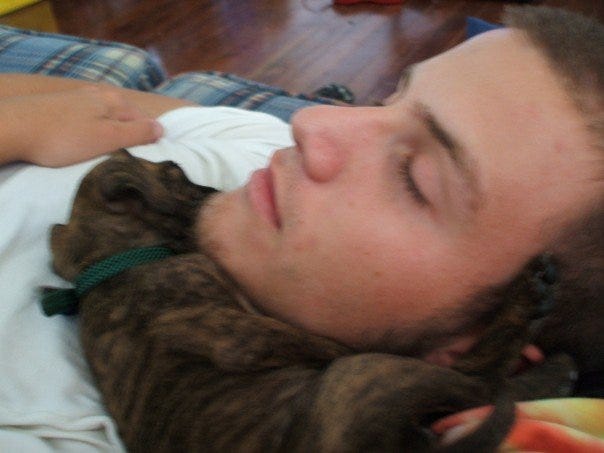

We’d gone to a dog shelter in West Columbia — not to get a dog, just to look. At least, that was the lie we had to tell ourselves to walk in the door. Once inside, we reasonably foresaw (but dared not openly acknowledge) that we would fall in love with a furry face and foreswear responsibility for any actions undertaken thereafter. Sure enough, we soon beheld the dog who would become Rilo, climbing to the top of a squeaking heap of puppies. We took turns holding her tiny, malnourished body and stroked her distended belly. (This moment is pictured in the top left photo above.) We jotted down the ID number around the nameless puppy’s neck — just in case — and went home.

What we found upon leaving is that we could not stop thinking about her and, furthermore, simply could not go on living without her. The next day, we returned to the shelter to see if Army Pup 956124 was still there.

And wouldn’t you know it: she was.

By some miracle, a whole day’s worth of people had walked into and out of the shelter, having made the same exact mistake we’d made: leaving without Rilo. Having been so unbelievably lucky once, what choice did we have but to bring her home?

If you want me

You'd better speak up

I won't wait

So you'd better

Move fast

-from "With Arms Outstretched" by Rilo Kiley and also Annie’s AIM away message at the time we started dating

In hindsight, what I now understand is that Rilo’s compulsion to climb atop her siblings was probably unrelated to any determination she might have had to go home with us. More likely, it was a manifestation of the profound anxiety that would define most of her life and, by extension, ours.

Before long, Rilo far outstripped her projected weight and grew into 50 pounds of bull-headed sinew. She was a boxer-pit mix who could run like a greyhound. She defied breed stereotypes by being a determined if inefficient swimmer. Rilo’s strength and athleticism were, by turns, something to marvel in and be terrified of.

When she got stressed out or bored during walks, Rilo attacked her leash. I do not mean that she playfully grasp the leash with her lips, as I’ve seen many golden retrievers do. I mean she would attack the leash, with little regard for the collateral damage inflicted upon the person holding it. One on one occasion, she snapped the leash in two, leaving Annie stranded in the middle of Pickens Street with a panicked dog who, quite literally, could not be brought to heel. Another time, Rilo was so startled by the sight of another dog that, in attempting to lunge toward it, she head-butted my leg, leaving a baseball-sized welt protruding from my left shin.

At dog parks, Rilo would grab hold of balls and absolutely refuse to let them go. One time in Chicago, some self-important doofus and his dog were ready to leave, but Rilo still had his dog’s ball and was defiantly pacing the perimeter of the park, ball locked between her jaws.

“Control your dog!” the man complained.

Believe me, buddy. I would if I could.

When it came time to leave a dog park, Rilo would evade capture at any cost. We had to develop elaborate plans to either trap her or, failing that, eventually tire her out.

No one, no thing has ever made me feel as physically overmatched as Rilo did. She had the capacity to create problems with life-or-death stakes. Problems that I sometimes felt utterly unequipped to solve. It was absolutely terrifying. In these moments, we contemplated (but dared not openly acknowledge) that it might be in everyone’s best interest if we gave Rilo up.

What happened instead is that we spent hundreds of hours doing comparative analyses of canine training methods, developed strong opinions about leashes and walking technique, and generally reoriented our entire lives around the needs of this stupid animal.

It was harder for Rilo to be a neurotic pain in the ass when she was exhausted (same tbh), so I began to take her with me whenever I ran. I was always worried about asking too much of her, but if anything it was Rilo who pushed me to go faster — she could push a six-minute mile pace in short bursts, especially if we were in sight of a dog park or some other canine-scented attraction. As she got in better and better shape, she required longer runs at faster paces to tire her out. At first, she would go three or four miles, but eventually she worked her way up to 10 miles at a sub-7 pace.

When we got back to our apartment, Rilo would make a mess of her water bowl and then lie down in the slobber-water cocktail she’d splashed along the hardwood floor. After a few minutes of lying on the cool ground and panting vigorously, she’d walk over and lick the salt off my legs. For me, running became more than just a means of staying in shape. It was an opportunity to impose discipline on a dog in desperate need of it. It was a shared experience with a friend. It was a reciprocal act of love.

With a lot of hard work and persistence, Rilo eventually became something approaching well-behaved. She stopped being a total menace on the leash and could be trusted to stay out of her crate while we were at work. As Rilo approached mid-life, she lost a step, and I had to leave her at home on runs. She still had regular walks, of course, and I’d take her running on an ad hoc basis, if she needed to be completely worn out before a road trip, vet appointment, or some other stressful event.

And so it went, for good 14 years and two less-good ones. I didn’t realize it at the time, but October 2021 was when Rilo had her last really good walk. Our house in Nashville was up for sale, and we had to make ourselves scarce all day during the open house. So Rilo and I spent the entire time walking the Shelby Bottoms Greenway.

It was hot out, and Rilo was ancient. Once it started raining, I went off-trail in search of a shortcut back to the car; we got lost and ended up walking eight miles. I was mosquito-bitten, covered in rain, sweat, and a thin film of gnats that had drowned on my skin. Before I could stop her, Rilo plopped down in a mud puddle to cool off.

In many ways, the walk was a terrible mistake. But once we pushed past the terrible mistake part, it turned into one of the best days Rilo and I ever spent together.

Rilo’s first brush with death came when she was almost 11. She suddenly stopped eating. She didn’t want to do anything except sleep in her crate, and her eyes were swollen shut. I wanted desperately for this not to be the end, not least because she was mere months away from getting to meet her first human sibling. If it was the end, though — if her condition wasn’t going to improve — I was grateful at least that putting her down would be an obvious decision, not one we’d have to dwell on and fret over.

But the bastard pulled through. After a procedure to remove an infected something-or-other in her neck, Rilo made a full recovery. She got to meet Hugo, and for five years Hugo came to know Rilo as both his friend and the primary reason why no one’s allowed to leave food unattended.

As soon as we completed our move to Ohio (in November 2021), Rilo’s health began to deteriorate — almost imperceptibly at first, and then seemingly all at once. First, there were the occasional squishy brown surprises left behind on the couch. Then, making it outside to pee became a hit-or-miss proposition. First, she was banned from the furniture, but it soon became a moot issue because she lost the ability to climb onto the furniture in the first place. By spring 2022, she stopped wanting to go on walks and her back hips began to sag.

Before long, Rilo was still enjoying her life but becoming a burden on those around her. She made so many messes that Hugo, then four years old, started repeating the words he heard Annie and I say most often: “Dammit, Rilo!” It finally became possible to stop resenting Rilo again after we swallowed our pride and put her in diapers.

Rilo would have bad days but then she’d bounce back and have better ones. Each time her baseline of peak health would dip a little lower. The vitality that had once been her hallmark was now slowly leeching out of her.

Our ideal death scenario was that Rilo would either go out in a blaze of glory or die peacefully in her sleep. But we would have no such luck. There would be no acute medical crisis riding to our rescue, making the choice to put her down an obvious one. It was just a steady deterioration that offered more questions than answers.

Does she still like being alive?

Isn’t it overly anthropocentric to assume that a dog no longer enjoys their life simply because they’re mildly disabled?

Shouldn’t we just end it now while she still has some dignity left?

Would I order a hit on my grandma just because she stopped making it to the toilet 100% of the time?

Are we devoting too much time and effort toward keeping her alive?

Is there something more we could be doing for her?

The irresolvable with problem with end-of-life decisions — particularly when the parties involved do not share a common language — is that it’s just too much power for one living creature to have over another. It is too big a thing to do, a thing that can’t be undone. If euthanizing Rilo ended up being just another terrible mistake, there would be no other side to push through to.

But recently Rilo lost interest in both food and houseguests, the last few things that still seemed to give her pleasure. We began to suspect, and even openly acknowledge, that the time had, at last, come. As soon as we spoke the words aloud, things started happening fast. Too fast.

Before we knew it, there was a $580 charge on our credit card to Little Veterinary Clinic. People who had known Rilo were receiving text messages, and some of those people were showing up at our doorstep to say goodbye. Suddenly, there was a dog-length, two-foot hole in the backyard and, at Hugo’s insistence, a makeshift gravestone. Strangers who vaguely resembled Annie and me were making a death plan that bore an eerie resemblance to Hugo’s birth plan. And at 10 a.m. on July 1, a vet and her assistant rang our doorbell, like DoorDash for assisted suicide.

First came the morphine injection. Within 10 seconds, all the tension vanished from Rilo’s brittle body, and she laid down, truly relaxed for the first time in months. According to the death plan, Hugo and I were supposed to leave the room before the anesthesia injection, but somehow we ended up staying. Then the third shot came, stopping Rilo’s heart instantly.

I’d been insisting that I did not think I would make a big scene. The dog I will remember has already been gone for a while. But when the vet said Rilo’s heart had already stopped, I lost it.

That stupid, persistent heart. The one that, for the past 16 years, had beat every second, like a promise and a threat. I can hardly remember a time when the needs of that heart and the creature that enveloped it hadn’t set the tempo of our days. It seemed inconceivable that it would never beat again.

When Hugo was three, we drove by a cemetery every day on the way to and from pre-school. One day, he asked me what “those statues” were. I told him that they were graves, and that it’s where some people put their bodies after they die. This was apparently the first time Hugo had been made aware that everyone, including him, is going to die.

He did not handle it well.

For months after this incident, Hugo would call me into his room after bedtime and complain that he couldn’t stop thinking about the cemetery. “I used to be happy,” he said, “before I found out what the statues were.”

As much as my heart ached for Hugo, part of me felt excited to have another companion to help shoulder the burden of this terrible knowledge. I wanted to say, “Welcome to the club brother, this news has been stressing me out for decades.”

Given how disruptive finding out about cemeteries had been, Annie and I were quite nervous about how Hugo was going to handle the experience of losing his first pet. We briefed him thoroughly on what was going to happen and allowed him to believe that he was making this decision with us.

During the procedure itself, Hugo was annoyingly cheerful, and part of me wished we’d sent him somewhere else for the day so that Annie and I could grieve without also having to parent. But when Hugo saw Annie and me sobbing, he seemed to finally understand what grieving was supposed to look like. Later, Hugo had some questions about what had happened to Rilo. (According to him, her soul is in “outer space” now.) He had questions about what was making me and Annie feel sad.

“It’s hard to think about Rilo not being part of our life,” Annie said.

And the child who used to lie awake at night, panicked about death — do you know what that adorable son of a bitch actually said?

“She still is.”

This is beautiful. Thank you.

Sorry for your loss of your friend. Dogs are very special and you had her for 16 years. But as your son said, you still have her in your life and will always have her. This was a well written tribute to what it means to have a pet who is an essential part of your family.