Dawn Staley's unlikely path to South Carolina

How a girl from the North Philly projects became one of the best in the world at two different occupations and decided to build a dynasty at South Carolina, of all places.

This story was originally published on Sept. 3, 2021, in the weeks following Dawn Staley winning a gold medal coaching in the 2020 Olympics. We’re re-running it today, in celebration of South Carolina’s advancement to the Final Four. This is your last chance to read it for free. Next week, it goes behind the paywall.

A few weeks ago, Dawn Staley won her first (and apparently last) Olympic gold medal as the head coach of Team USA. So even though the football season starts tomorrow, today’s newsletter is about basketball. Part of that is down to my penchant for contrarianism, but mostly it’s because writing this story was a more challenging undertaking than I anticipated, and it genuinely took two weeks of hard work to do all the research and writing.

Turns out, there was a whole lot I didn’t already know about Dawn Staley and her life before she got to South Carolina. Maybe that’s the case for you as well.

North Philadelphia, born and raised

In April 1996, Estelle Staley was on the No. 33 bus in Philadelphia going east on Market Street when she caught sight of her youngest daughter.1

She blurted out, “Oh, my God!”

By herself on the bus, she started crying, she said.

Her daughter, Dawn, was still a few blocks down the street, nine stories high on a mural, a basketball player in motion, her jersey billowing, mouth open.

Her mother could see the mural as soon as the bus turned the corner at City Hall. People on the bus saw her tears. They asked her what was the matter.“That's my baby up there,” she told them.

The 100-foot mural of Dawn Staley, Team USA’s star point guard, had been commissioned by Nike in advance of the 1996 Olympic Games. The accompanying text read, “Born in Philadelphia. Grew up on the corner of 25th and Diamond.” The cross-street is a reference to the Hank Gathers Recreation Center and the outdoor courts where Dawn and countless other North Philly kids played growing up.

The Staleys ended up in Philadelphia only after Estelle Staley became one of an estimated six million black Americans who fled the South during the reign of Jim Crow. Estelle left her hometown of Orangeburg, South Carolina in the late 1950s and, with her husband Clarence, she raised her five children in a three-bedroom rowhouse in the Raymond Rosen housing projects in North Philadelphia.

In the span of a few decades, the Staleys became part of the scenery — literally, in the case of Dawn’s Nike mural. When South Carolina athletics director Eric Hyman was luring her away from Temple University in 2008, he described a scene that can’t help but summon comparisons to Sylvester Stallone running through the streets of Philly in Rocky II. As they walked the streets of North Philadelphia, Hyman said Staley was approached by locals, hugged friends, and “waved to passing cars whose passengers pleaded with her not to leave her hometown.”2

Other people said no to the South Carolina job before Dawn Staley got the offer. But at least some of that had to do with Hyman’s initial assumption that there was no prying Staley away from Temple. The conventional wisdom on Staley was that Philadelphia was so ingrained in her DNA that the only job she’d even think about leaving for was her alma mater, the University of Virginia.

But the conventional wisdom was wrong — a fact Hyman only found out through an unsolicited tip from a friend of Steve Spurrier. You see, the son of one of Spurrier’s longtime golfing buddies was Staley’s agent. It’s one of those stories that sounds like a deranged message board conspiracy involving flight trackers and cash offers for houses on Lake Murray. But in this case at least, it seems to check out. 3

While Dawn’s love for Philadelphia ran deep, her agent knew that it wasn’t the only thing that made her tick. Dawn was eager for the chance to go toe-to-toe with (and eventually topple) SEC legends like Pat Summit. But one advantage South Carolina had that none of the other 11 SEC schools could claim was geography: Dawn also wanted to help her mother live closer to her friends and family in her hometown of Orangeburg, South Carolina.

The darkness before the Dawn

It took Estelle Staley longer than most people in Dawn’s orbit to fully appreciate just how good she was at basketball. Between working and caring for her family, Estelle didn’t have time to notice that her youngest daughter was a basketball prodigy. When Dawn was about eight years old, a coach at Dawn’s elementary school stopped by and asked her mother, “Mrs. Staley, did you know Dawn can really play basketball?”

“No,” she said.

“Well, she can really, really play,” he answered.4

Dawn would later credit the development of her game to playing on the courts at 25th and Diamond against other North Philly kids. By the time Dawn was a freshman in high school at basketball powerhouse Dobbins Tech, college recruiters were already on the scent. When she was a senior, USA Today named Dawn the national high school player of the year.

“Dobbins coach Tony Coma called me one day and told me I should come up and watch Dawn play,” Estelle recalled later. “When I did, I thought, ‘My God, she is good.’ But I still didn't think she'd make a career out of it.”

And how could she have?

When Dawn Staley drew her first breath, the job of professional basketball player would not exist in the United States for another 26 years. The job of collegiate women’s basketball coach did not exist hardly anywhere, and certainly not at the University of South Carolina.

In 1970, the year Staley was born, the USC women’s basketball program was a rag-tag operation called the Carolina Chicks. The 13 players and volunteer coach supported the team with their own fundraising efforts and, in some cases, their own funds. Despite their meager resources, the Chicks nevertheless managed to field a nationally competitive team. But however successful they might have been, the athletics department refused to let the Chicks play or practice in the Carolina Coliseum.

“We were told no, absolutely not,” said Linda Webb, a founding member of the Carolina Chicks. “So I felt shunned.”

It took a literal act of Congress for USC to reconsider its position. Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 banned sex discrimination in federally funded education programs, effectively creating the legal and institutional infrastructure upon which the sport we know today was built. Compliance with Title IX would not become mandatory until 1978, but USC was one of many institutions that expanded opportunities for women before the deadline arrived. And so, in 1974 the Gamecocks sponsored a varsity women’s basketball team for the very first time.

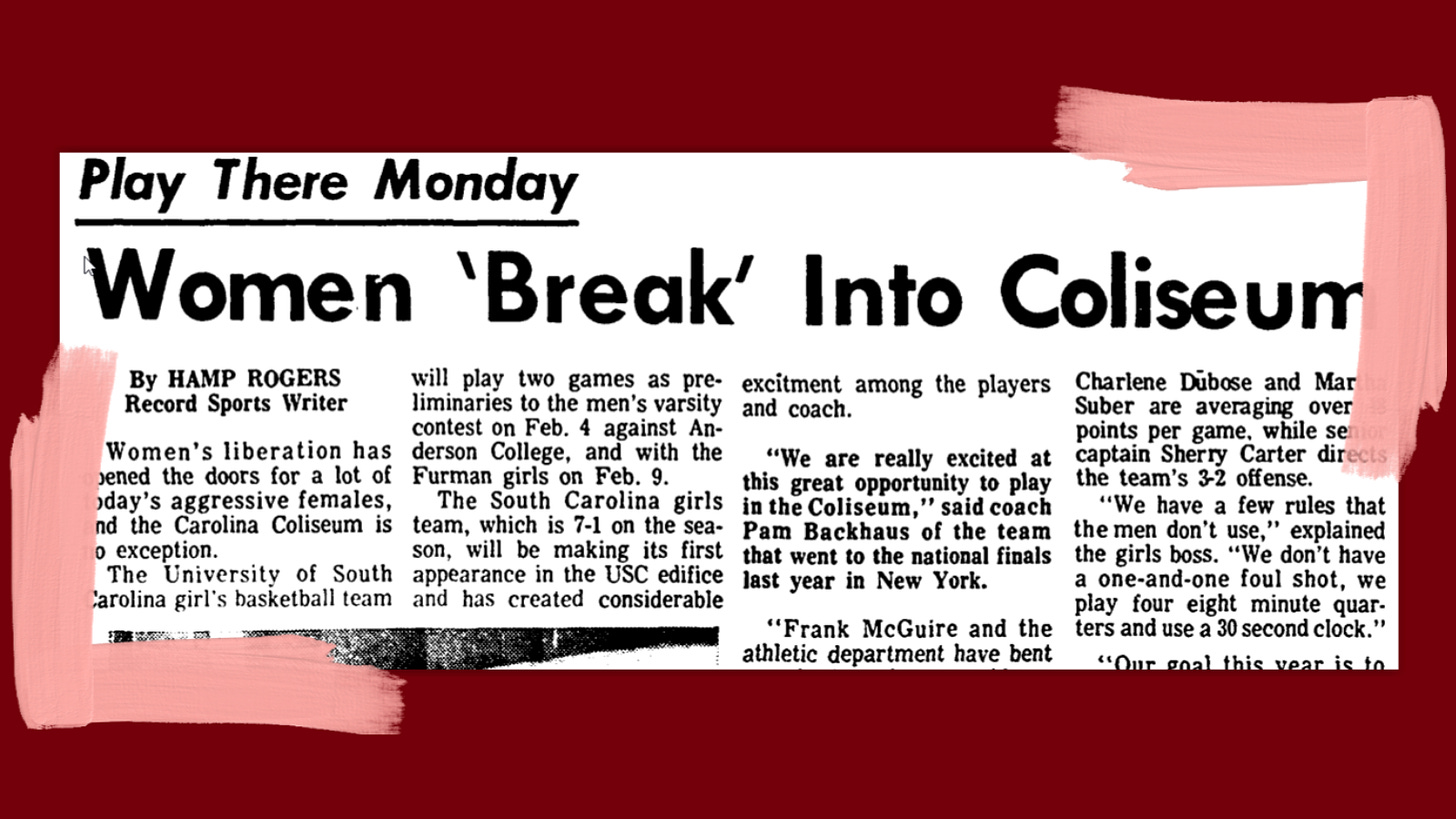

The name Carolina Chicks stuck around for a few years, but with official USC sponsorship came a professional coach (Pam Backhaus) and permission to use the Coliseum. When the Chicks first started sharing a venue with Frank McGuire’s team, the Columbia Record wrote, “Women’s liberation has opened the doors for a lot of today’s aggressive females, and the Carolina Coliseum is no exception. The University of South Carolina girl’s basketball team will play two games as preliminaries to the men’s varsity contest on Feb. 4 against Anderson College, and with the Furman girls on Feb. 9.”

The Chicks competed in the Alliance for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women, which was a kind of separate-but-equal version of the NCAA. Divisions II and III folded into the NCAA in the late 1970s, but Division I held out until 1982, with internal factions of the AIAW bitterly divided over the question of whether to remain independent.

When South Carolina joined the Metro Conference in 1983, the so-called Lady Gamecocks finally had a league of their own. Entry into the Metro coincided with what was considered, until quite recently, the golden age of South Carolina women’s basketball. Coached by Nancy Wilson — who will be inducted into the USC Sports Hall of Fame this October — South Carolina made it to the NCAA Tournament in five of six seasons, winning three conference titles in the process. But Wilson’s program disintegrated upon impact with the SEC, and after winning only 13 conference games in her last six seasons, Wilson resigned in 1997 under pressure.

Wilson’s successor, Susan Walvius, recalled that “there was a time when not only the best players in South Carolina chose to play at USC, but also the best prospects in the country. The way I remember South Carolina as a player was as one of the best programs in the country.”

But by the end of Walvius’ tenure, an entire generation of Gamecock fans had only ever known a Lady Gamecock program hopelessly consigned to mediocrity. With women’s basketball still a net drain on profits, there might have been every reason to think athletics director Eric Hyman would seek to replace Walvius with a warm body who would meet the minimum requirements of the position — and little more.

Instead, Hyman sought and obtained approval from the board of trustees to pay top dollar for a living basketball legend who also happened to be the best young coach in the sport.

The standard-bearer

University of Virginia head coach Debbie Ryan enjoyed more than three decades of success during her legendary career, but none were more productive than the four years Staley served as the Cavaliers’ point guard. From 1988 to 1992, UVA won two ACC Tournament championships, two regular season ACC titles, and made it to the Final Four on three different occasions. Since Dawn Staley graduated three decades ago, the Cavaliers haven't been back to the Final Four once.

Staley left UVA as the two-time reigning Naismith College Player of the Year, having set the NCAA record for career steals and breaking UVA records for points and assists. She was the best player in her sport, just entering the prime age of her career. By the end of her playing days, Staley would be widely regarded as one of the best basketball players America has ever produced. But at the precise moment she entered the workplace in 1992, “professional women’s basketball player” was still not an occupation that existed in the United States.

In order to continue plying her trade on the basketball court, Staley went to play for a team in a small town in Southwest France. Later, she played professionally in Italy, Spain, and Brazil. And yet even as she was forced to immigrate to Europe and South America to find work, Staley was on her way to becoming a household name because of the way she played while representing the United States. In 1994, Staley’s outstanding performance at the FIBA World Cup earned her the first of two USA Basketball Female Athlete of the Year awards. Two years later, Staley led team Team USA on a 60-game winning streak that ended with a gold medal in the Atlanta Olympics.

At the Atlanta games, America won its first team gold in gymnastics, won gold in the first-ever women’s soccer competition at the Olympics, and the women swimmers’ seven gold medals were bested only by the male track athletes’ 10 gold medals as the greatest contribution to the Olympics-best 44 gold medals. The U.S. women’s basketball gold medal game victory over Brazil closed out the ‘96 Olympics, an exclamation point on what ended up becoming a month-long celebration of American female excellence.

“The result, a 111-87 victory over Brazil in the gold-medal game,” wrote Dave Teel in the Newport News Daily Press, “punctuated nearly three weeks of unprecedented success and exposure for American female athletes - success and exposure that will resonate for years.

“Just consider the circumstances surrounding Sunday's contest. NBC television dictated the 6:30 tipoff time to give the network the largest possible lead-in audience to the closing ceremonies. NBC could have had men's basketball. NBC could have had track. NBC chose women's basketball.”5

As the air of wonder surrounding the 1992 Dream Team began to recede, the women’s basketball team proved, for some, a compelling foil to the men. Where they once gazed upon the likes of Charles Barkley and Scottie Pippen wearing the same uniform and saw an historic assemblage of talent, critics were now more likely to see overpaid, disinterested superstars. But the women, still fighting and clawing for recognition and the right to earn a living in their home country, gave off an altogether different vibe.

“This was the feel-good team of this patriotic summer festival,” wrote Bernie Miklasz in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “They played the best basketball, drew the largest and most enthusiastic crowds, had the most fun, shared the most togetherness, converted more new fans and were easily the most entertaining … I'd rather watch this than $121 million worth of same-old Shaquille O’Neal dunks. The postgame celebration touched the heart. The players ran a lap, waving to the crowd. Teresa Edwards, Dawn Staley and [Jennifer] Azzi did synchronized cartwheels. The 12 players hugged and cried together, the way sisters do. This was real emotion.”6

At the start of the 1996 Olympics, many of the Team USA players, including Staley, were contracted to play in the American Basketball League, which was set to begin play later that year. Others were biding their time, waiting to see what the inchoate WNBA might have to offer. Staley played two seasons with the Richmond Rage before the ABL folded. At the age of 29, she was selected as the ninth overall pick in the WNBA Draft.

From 2000 to 2006, Staley pulled double duty as a six-time WNBA All-Star and head coach of the Temple Owls. In the same year she guided Temple to a sweep of the Atlantic-10 regular season and conference tournament championship, she won her third Olympic gold medal and was named, for the second time, USA Basketball’s Female Athlete of the Year.

At the opening ceremony of the Athens Olympics, the captains of each American sport selected Staley to carry the United States flag during the parade of nations. Her selection was the formal manifestation of an idea that would someday make Dawn well-suited to coaching Team USA: her peers saw her as a leader of leaders.

As for the act of bearing the flag itself, Dawn described it this way:

When the day arrived, the U.S. delegation gathered in this holding area, and a really serious-looking gentleman approached me … He said, “We are the USA. Keep your head up. Walk prideful, and never dip the flag.” As I walked into the stadium, I was anxious and very aware I was walking alone. In complete awe, I pushed my shoulders back, looked straight ahead, firmed my grip on the flagpole and walked strong. As I neared the first curve, I thought about how far I’d come from the Raymond Rosen housing projects in North Philly. I wondered if the boys I grew up playing with at 25th and Diamond knew how grateful I was to them. I wondered if they knew how much they taught me, how tough they made me, and how big they made my game.

As I entered the second curve, I heard chants of “U-S-A, U-S-A.” I could feel the celebration building behind me. I looked over my left shoulder and saw my teammates. With my motion, the flag swayed a little, so I quickly steadied it. Although I was flattered by the honor of being the flag bearer, part of me really wanted to be with my team. It made me remember my first gold medal in 1996 and how we had to sacrifice a year of our life to be on the national team.

My mom didn’t make the trip to Greece, but I knew she was watching. She could see me. I was sure she had a house full of people and cooked a spread. Whoever was there was probably invisible to my mom, as I knew she was glued to to the television. I knew that every step I took, she took with me.

As I neared the end of the last straight and saw an usher signaling for me to enter the field with the other countries. I took one last look around, looked behind me and thought, “Unbelievable. The best athletes in the world are following a girl from the projects of North Philly.” A shallow smile crossed my lips as I looked up and whispered, “Thank you.”

The next Olympics, in 2008, would be the first since 1992 that did not feature Dawn Staley on the court. She was, however, on the sidelines: as an assistant coach for Team USA. In the run-up to the Olympics, Staley had been flying back and forth from China to negotiate contract terms with Eric Hyman. And by the time the Beijing games began, she had been introduced as the next head coach at South Carolina.

Following Walvius’s forced resignation, Hyman decided that he wanted to spend the money required to make the women’s basketball program a success. So, with approval from the board of trustees, he did. With incentives, Staley’s first contract came in just shy of $1 million per year, and her base pay was equal to Darrin Horn’s and almost double Ray Tanner’s. Walvius’s first contract in 1997, by comparison, was only five figures.

In Feb. 2018, during a break in the action at a home game against Vanderbilt, A’ja Wilson stood at half court to be recognized for collecting her 2,000th career point and 1,000th career rebound. Standing next to her was Staley, who had just coached Wilson to a national title the previous year and would coach her to a gold medal in 2021.

With them was Edith Cook-Burkett, who had been a star at Irmo back in the early 1970s and had, at the suggestion of a friend, tried out for the Carolina Chicks when she was a senior at USC. Cook made the team and began the year as a starter. And so, forty-two years earlier and two blocks down Lincoln Street from where she stood with Staley and Wilson, Cook became the first black player in the short history of the women’s basketball program.

Around the same time, six-year-old Dawn Staley was showing up to the courts at 25th and Diamond with her own ball, so that the boys would have to play with her. Pretty soon, her elementary school coach would show up at her mom’s door to tell her that her that Dawn was really, really good at basketball. Even though there were no professional women basketball players for Dawn to model her game after (instead, she idolized Mo Cheeks) and no black coaches for her to look up to, the doors were beginning to open. In many cases, Dawn was one of the people responsible for kicking the door open in the first place. And now, the women she’s held the door open for are becoming as much a part of Columbia’s scenery as she was in Philadelphia — literally, in the case of the A’ja Wilson statue that greets visitors to the Colonial Life Arena.

For the past 14 years, Dawn Staley has been the most stable presence in South Carolina athletics. When her next contract extension runs out, she’ll have been coaching at USC longer than Ray Tanner did — and there’s a decent chance she’ll have at least as many national championships as he did by that point, too. Though Dawn was born into a world in which the job she holds did not exist, now there are high schoolers who have never drawn breath in a world in which the best women’s college basketball coach worked anywhere other than USC.

Discover Wines You Love

Bright Cellars is the monthly wine club that matches you to delicious wines, tailored to your tastes. Created to not only deliver excellent wine, but to also give the added bonus of learning about your wines and own tastes.

Get 50% off the first 6 bottle order!

Mike Jensen, "Staley hits heights in hometown,” Philadelphia Inquirer, The (PA), April 13, 1996

"Staley brings instant credibility,” State, The (Columbia, SC), May 11, 2008

Ron Morris, “Fate, Spurrier brings Staley to USC,” State, The (Columbia, SC), May 9, 2008

Ray Parrillo, "Queen of the court,” Philadelphia Inquirer, The (PA), August 13, 2006

David Teel, “These were games for our women,” Daily Press (Newport News, VA), August 5, 1996

Bernie Miklasz, “Truly dreamy basketball,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 6, 1996